Every day, millions of Indians donate clothes. From overflowing bins in apartment complexes to corporate drives and online returns, the assumption is that these garments will find a second life.

But the reality is far more complicated. Textile Waste Recycling in India is constrained by systemic gaps, operational inefficiencies, and human challenges. In fact, only a small fraction of donated clothing is truly recycled into new fibers. Most garments are downcycled into rags or industrial stuffing, exported for resale, or, in the worst cases, end up in landfills or informal incineration.

In this article, we trace the journey of clothes after collection, share what we’ve observed working on the ground, and explore how meaningful recycling can actually be achieved.

1. Walking Through the System

We’ve spent hours in warehouses stacked with used clothes, visited bustling sorting centers, and watched garments move through multiple hands. The reality is sobering: what looks like an organized donation system often masks huge losses.

Most people think dropping off clothes is enough. But the journey is messy, human-dependent, and rarely ends with garments being recycled. Many donated items are exported, resold, or shredded for industrial purposes. Very few make it back into fiber form that is required to produce new clothing.

What we’ve learned is that collection alone cannot solve the problem. Effective textile waste recycling requires a system designed end-to-end, from collection to fiber recovery.

2. Collection: More Complex Than It Seems

Clothes reach recycling streams through:

- NGO campaigns and donation drives

- Drop-off bins in neighborhoods, malls, or offices

- E-commerce returns and unsold stock

- Informal collectors and ragpickers

At first glance, collection seems simple, but it heavily influences the success of textile waste recycling.

We’ve noticed:

- Many donations are worn-out, torn, or contaminated. Even if a garment looks fine from afar, dirt, dampness, or odor can prevent it from being recycled.

- Informal collectors are crucial in India’s system. They pick up clothes from neighborhoods, bundle them, and sell them to traders. While they extend garment life, they also remove transparency. We can’t always track where the material ends up, and recycling opportunities are often lost.

- Warehouses may boast high tonnage, but the actual recyclable fraction is often far smaller than the total collected.

Decisions made at this early stage directly determine how much material can later be reused, recycled, or safely processed. When garments are damaged, mixed, or poorly stored, recovery options shrink, and more material ends up being downcycled or discarded.

3. Sorting: Where Reality Hits

Sorting is where the true challenge begins. Workers in sorting centers handle thousands of garments daily, a critical step in effective textile waste recycling, separating them for reuse, downcycling, or recycling.

Here’s what we’ve observed:

- Clothes are first separated by fabric type: cotton, polyester, wool, or blends. Blended fabrics are notoriously difficult to recycle.

- Next, the condition is assessed: wearable, repairable, or beyond use. Disruptors such as zips, buttons, and other attachments are removed, and even minor contamination can disqualify a batch from mechanical recycling.

- Up to 60% of collected garments are often categorized as low quality. These are either downcycled or discarded.

Sorting is labor-intensive, and human factors, like fatigue, turnover, and inconsistent training,directly affect how much material is recovered. Technology can help, but human judgment is still key when it comes to assessing wear, contamination, repair potential, and real-world reuse value; factors machines still struggle to read accurately.

4. Paths After Sorting: What Actually Happens Next

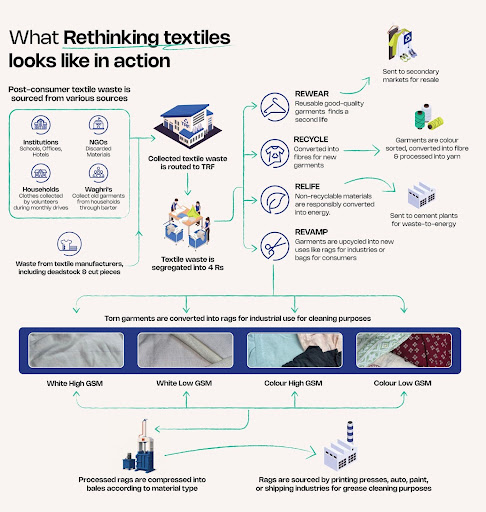

After sorting, garments are routed into clearly defined recovery pathways based on quality, material type, and recyclability. In practice, this follows a structured 4R framework: Rewear, Recycle, Relife, and Revamp supported by industrial processing streams.

4.1 Rewear (Secondary Markets for Reuse)

High-quality, wearable garments are routed to secondary markets for resale. These items are cleaned, graded, and distributed to local or export resale channels, extending their usable life.

While rewear does not regenerate fibers, it plays a critical role in reducing immediate textile waste and maximizing the functional lifespan of clothing. However, reuse alone is not recycling; it only delays the garment’s entry into the waste stream.

4.2 Recycle (Fiber and Yarn Recovery)

Garments suitable for material recovery are processed for recycling wherever possible. This includes:

- Segregation by color and material type

- Removal of buttons, zippers, and non-textile components

- Shredding and processing into yarn or fiber for new textile applications

Only garments that meet strict quality and contamination standards can enter this stream. In practice, this represents a small fraction of total collected volume, as blended fabrics, elastane, and contamination limit recyclability.

This is the pathway required to produce new textile fibers but it remains constrained by material complexity and infrastructure limitations.

4.3 Re-life (Industrial Rags and Utility Products)

A significant portion of non-wearable garments are converted into industrial cleaning rags and wiping cloths. Torn, stained, or heavily used garments that cannot be resold or recycled into fibers are:

- Sorted by color and GSM (fabric thickness)

- Cut and processed into cleaning rags

- Compressed into bales based on material and quality

These rags are supplied to industries such as printing, automotive, painting, shipping, and heavy manufacturing for grease, oil, and surface cleaning.

This pathway preserves utility value and diverts material from landfills, but permanently removes textiles from the apparel production cycle.

4.4 Revamp (Energy Recovery for Non-Recyclables)

Textiles that cannot be reused, recycled, or repurposed into rags are routed to waste-to-energy or co-processing facilities.

These materials are converted into energy through controlled industrial processes, providing a final recovery option for non-recyclable textiles. While this is not material recycling, it ensures that unusable garments do not end up in open dumping or informal burning, reducing environmental harm.

What This Means in Practice

Across real-world operations, the majority of garments flow into rewear and re-life (rags and utility products), while only a limited share reaches true fiber-to-fiber recycling.

Our field experience shows that less than 10% of collected garments typically reach fiber recovery suitable for producing new textiles. The rest are managed through resale, industrial reuse, or energy recovery pathways.

This structured routing ensures that every garment is directed to the highest possible value stream even when true recycling is not technically or economically feasible.

5. Structural Challenges

We’ve noticed multiple systemic barriers:

- Material complexity: Blended fabrics, spandex, and multi-layer garments cannot be mechanically recycled. Chemical recycling exists but is expensive and limited.

- Contamination: Dirt, moisture, or minor damage can make an entire batch unsuitable.

- Limited infrastructure: Very few facilities exist in India to support effective textile waste recycling and convert old textiles into fibers for new garments.

- Informal market dominance: Informal networks handle a significant share of clothes. While they support reuse, traceability and recycling potential are often lost.

- Economic constraints: Recycling is expensive. Without demand for recycled fibers, garments are downcycled or discarded.

We’ve seen even the most carefully collected clothes fail to become fibers due to these structural bottlenecks.

6. Human Factors: The Invisible Barrier

Textile recycling is heavily reliant on human labor. Collection, sorting, and transport require skill, attention, and consistency.

We’ve observed:

- High turnover in sorting centers reduces continuity and expertise.

- Training gaps mean recoverable items are sometimes discarded.

- Incentives often reward speed or tonnage, not recovery quality.

Aligning human effort with material recovery is critical for successful textile waste recycling. When workers are supported, trained, and incentivized properly, recovery improves noticeably.

7. Measurement and Accountability

Tracking is another weak point. Most programs measure the volume collected, not what is actually recycled.

Few systems track:

- Material lost during sorting

- Rejection rates at facilities

- End destinations for downcycled garments

We’ve implemented stage-wise tracking in several projects, and even small improvements in measurement lead to significant gains in recovery. Transparency creates accountability.

8. Behavioural Misalignment

Donors assume quality is automatically maintained; collection agencies equate tonnage with success. This mismatch reduces the system’s efficiency.

We’ve noticed that small interventions, like educating donors on clean, neat clothes and providing feedback about garment fate, significantly improve recovery. Behaviour follows system design, not intention alone.

9. Practical Solutions That Work

From our fieldwork, effective textile recycling requires a coordinated set of interventions:

- Design for recyclability

Garments should be made from a single material wherever possible. Mono-material clothing is far easier to process into new fibers, while blended fabrics are challenging and often cannot be recycled mechanically. Thoughtful design from the start increases recovery potential. - Segregated, high-quality collection

Protecting clothes from dirt, moisture, and damage during collection preserves their reuse or recycling potential. Well-organized collection ensures that a higher proportion of garments can move safely through sorting and processing. - Skilled and motivated sorting workforce

Workers need training to assess garment quality, remove disruptors like zips and buttons, and handle items carefully. Incentives tied to recovery outcomes, not just speed or tonnage, help maximize the amount of material that can be recycled. - Infrastructure investments

Technology-assisted sorting improves efficiency and accuracy, especially when managing large volumes of clothing. While machines help, human judgment remains crucial for contamination checks, repairability assessment, and quality evaluation. - Market creation

Without demand for recycled fibers, even carefully collected and sorted garments may be downcycled or converted to energy. Creating reliable markets ensures that recycling remains economically viable and encourages more systematic recovery. - Traceability and transparency

Tracking garments from collection to recycling allows programs to measure outcomes, identify bottlenecks, and improve processes. Transparency builds accountability and enables continuous system optimization. - Public education

Donors play a key role in recovery. Educating them on clean, well-prepared, and organized clothing can significantly increase the amount of material suitable for recycling, making the entire system more effective.

When these interventions work together, textile recycling rates rise substantially, creating real environmental, social, and economic impact.

10. Why This Matters

India produces millions of tons of textile waste annually. Mismanaged recycling means lost resources, landfill pressure, and pollution.

With the right system design systems that address human, operational, and economic realities, we can recover far more value, reduce environmental harm, and build a true circular textile economy.

Donation alone is not enough. Real impact comes from systemic interventions and operational rigor.

Facing the Reality

Textile waste recycling can only work when we address operational bottlenecks, infrastructure gaps, human factors, and economic realities. Collection is only the first step. To create true impact, we must design systems to preserve material, maximize recovery, and ensure accountability at every stage.

At ReCircle, we work across the textile ecosystem, from collection to sorting to recycling, to ensure that every garment is handled responsibly. We focus on measurable recovery, operational transparency, and real-world solutions that increase the impact of textile recycling.

Because the real value of clothing is realized not when it is donated, but when its journey after collection is managed intentionally.

FAQs

Q1. Do donated clothes get recycled into new garments?

A: Rarely. Less than 10% of collected clothes in India are turned into new fibers. Most are resold, downcycled, or discarded.

Q2. Why is textile recycling in India so inefficient?

A: Challenges include:

- Blended and multi-layer fabrics that are hard to recycle

- Contamination of clothes

- Limited recycling infrastructure

- Informal networks handling most donations

- Low market demand for recycled fibers

Q3. What happens to clothes after sorting?

A: Clothes are:

- Resold locally or internationally if high quality

- Shredded into rags, mattress stuffing, or insulation (downcycling)

- Clothes are either recycled into new fibers or sent to waste-to-energy facilities if they cannot be recycled.

Q4. Can donors improve the recyclability of their clothes?

A: Yes. Donors can:

- Ensure clothes are clean and dry

- Separate items by type or material when possible

- Avoid donating heavily blended or damaged items

Q5. How does ReCircle improve textile waste recycling?

A: We focus on:

- High-quality collection and monitoring

- Skilled sorting and segregation

- Connecting material to verified recycling or downcycling channels

- Transparent reporting and measurable recovery